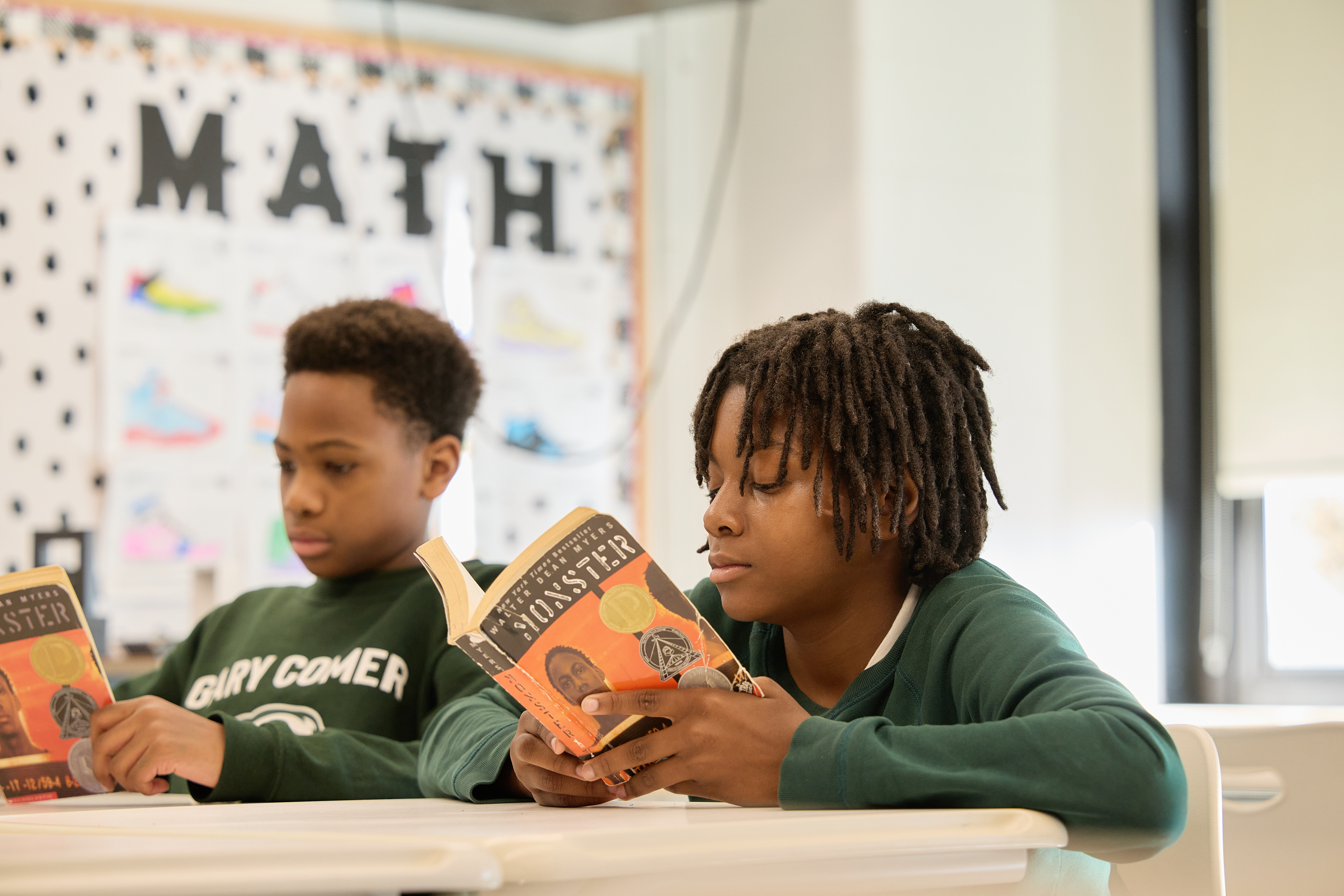

What is it really like to experience English Language Arts (ELA) as a middle schooler? To get an inside look, we spoke with Gary Comer College Prep English teacher Patrice Barnes and a few students in her class about their classwork and some of the books they read this year. Their words paint a picture of a class that sparks creativity and deep thinking.

Pushing Students to Read and Think Critically

Reading isn’t a race. That’s one of the first lessons that stuck with Kristan Thompson (KT), an 8th grader. At the start of the year, he rushed through assignments, missing key details and struggling to understand the material. But something shifted.

“I had to really just sit down and I had to keep rereading the work so I could understand it. When I say I have to be more strategic and don’t rush… if you rush, you are not going to understand the work for real and you are not going to get the grade that you really want,” KT said.

Slowing down allowed KT to develop not just his reading comprehension, but his critical thinking skills. Triston Smith, another 8th grader, mentioned how annotating, rereading, and asking questions gave him tools he could apply beyond ELA— even in math class.

There’s no doubt that ELA pushes students to think critically. But, while it can be challenging, students emphasized that it’s a good kind of challenge.

Diving Into Lived Experience and History Through Literature

Understanding different points of view is critical, especially when the characters’ lives intersect with those of our students. Books like Long Way Down, Monster, and The Central Park Five don’t shy away from difficult truths. They resonate because they reflect the realities many young people face—and they give students a safe space to process them.

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

Barnes specifically selects books that students can relate to. Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds, a book that explores the impact of gun violence, was chosen after extensive research and reading reviews, as well as Barnes’ personal connection to the topic as someone who has lost a loved one to gun violence.

KT connected to the book in a similar way.

“What happened in the book (Long Way Down)… most of the people in my community, of my race and color and my age, have been through something like that,” KT said.

On top of being relatable, the book is written as a collection of free-verse poems. As a result, Barnes has seen scholars who struggle with reading feel more successful with this unit.

“Long Way Down can spark their interest in reading, not just for class, but for themselves, too. I have had multiple scholars from previous graduating classes come back to tell me how great the book was or how they referenced it in their freshman coursework,” Barnes said.

The Central Park Five by Anna Burns

In another unit on The Central Park Five by Anna Burns, students learned about the real-life story of the Central Park Five. Barnes also combined this with the TV miniseries When They See Us by Ava DuVernay. Students didn’t just read or watch—they investigated, asked questions, and dove into the complexities of wrongful convictions.

“It’s important because it can help us in the real world… we can know our rights and know what they put Black people our age and our race… through and how they were doing it,” KT said.

Barnes explains that students are curious about real-life stories. In this unit, she used The Central Park Five and When They See Us, but, in the past, she also included Of Mice and Men.

“Oftentimes, scholars can feel disconnected to content from long ago with characters who are different ages. In this case, I hoped that students were able to connect to the story more because most of my students are the same age and race and come from a similar city as the Exonerated Five when they were younger,” Barnes said.

These texts foster a powerful connection between students’ lived experiences and what they’re learning in class. Whether it’s the fear of being misjudged, the weight of peer pressure, or the strength it takes to make the right decision, students are engaging with big questions—and sometimes, rewriting the endings themselves.

Creative Projects That Bring Stories to Life

When students read Long Way Down, they were asked to write their own endings. Some imagined the main character following through with revenge. Others envisioned him walking away, choosing a different path.

“I would’ve went back upstairs, for the future of my life. ‘Cause like I feel like my life is bigger than some type of revenge,” Triston said.

Barnes loves this project because it “highlights class content, personal voice, and requires students to pay attention to the nuances of the book.” The project consistently produces some of their best writing during this unit, Barnes said.

“The students got really creative with their endings, and even added details and characters that I never even considered,” She added.

ELA at Gary Comer Middle School is more than just reading and writing—it’s about discovery, engagement, and connection. Whether through analyzing historical narratives, debating character decisions, or rewriting endings, students are challenged to think critically and creatively.

To Barnes and other English teachers at Noble, this work isn’t abstract, despite the sometimes abstract nature of literature. It’s preparation. It’s protection. It’s empowerment.