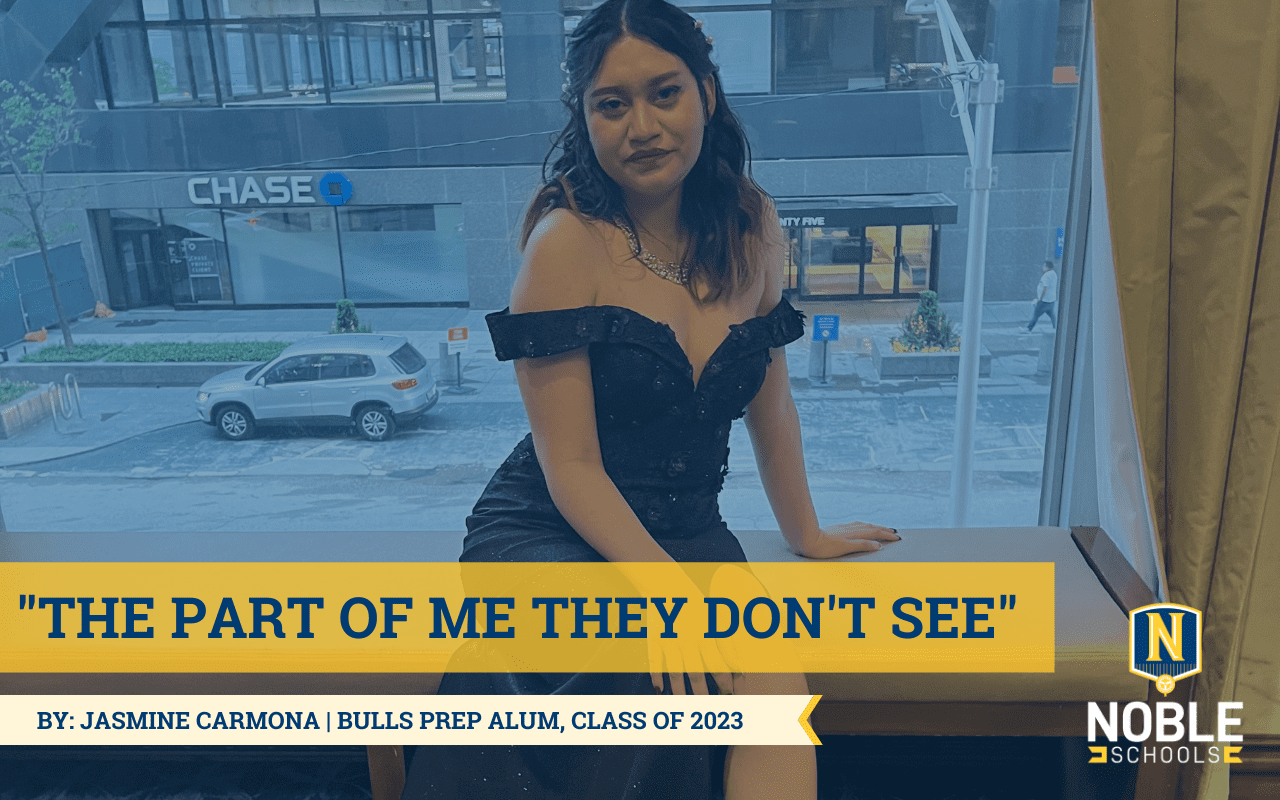

BY JASMINE CARMONA | she/her | Chicago Bulls College Prep Alum

How does it feel to have an invisible disability? To many, I live a perfect life. I have a wonderful family, a supportive boyfriend, and my caring pets. However, underneath all of that, my disability is a major part of my identity, and I feel like it deeply explains me and my life. No one can see what is “wrong” with me* – they only see the parts of me that are considered “normal” in our world. However, I want to share the other part of me – part of me that our world often ignores.

*I say this not to characterize my disability as though it is something that is wrong with me, but because I want to point out how others perceive my disability in an ableist manner once they are aware of it.

My name is Jasmine Carmona and I am a recently graduated senior from Chicago Bulls College Prep. I was diagnosed with Graves’ Disease at 4 years old. Graves’ Disease is a thyroid condition that affects a person’s hormones and can cause many other health issues. My thyroid was removed shortly after my diagnosis. To this day, there is still no understanding of how I got this condition. After the surgery, I continued to push forward even during the struggles I had afterwards –I remembered even being bullied due to my appearance that is associated with Graves’ Disease (dark circles, bulging eyes, lightweight). Through all of it, I found myself surrounded by my supportive family. However, my life changed again when I began to suffer from intense pain in my jaw.

Jasmine posing at her prom.

Right before high school, I was diagnosed with Ameloblastoma, a rare, non-cancerous tumor that is found in the jaw. The tumor had no connection to my Graves’ Disease, so again, I had a diagnosis with no direct cause.

The doctors informed me of the urgency of my surgery and it was planned for February of the following year – my birthday month. The surgical procedure was planned out: they would remove my leg bone (fibula) and use it to replace my jawbone. Then, the doctors would remove my teeth and surgically repair my face. The procedure took an entire day and lasted over 10 hours. After having my fibula removed, I couldn’t walk for a while. I was given the option of crunches or a walker to help with my walking. I opted in for a walker as I researched ahead what would be best for my rehabilitation. The recovery process didn’t last long. I spent a month at home and shortly after I went back to middle school. Fast forward, I’m in my freshman year of high school at Chicago Bulls College Prep.

Jasmine with her pet parrot, Scooby.

My freshman year was filled with medical trauma as I was still recovering from the 12-hour procedure. I was drained mentally and physically and only one teacher noticed: my freshmen year gym teacher, Coach Cain. He was very supportive and understood my medical issues. During this time period, I was doing physical therapy to recover, but then that and my freshman year were cut short due to COVID-19. Just like that, my only resources for recovery were halted. I didn’t have the motivation to exercise my legs at all during quarantine. When I returned to school, my leg was weaker than before. I couldn’t run nor could I do anything. It wasn’t noticeable, but at times, the more I walked, the more I would limp.

During this time, Coach Cain left and a new teacher took over. I explained to her my medical issues and restrictions. At first, I had no issues in class but I began to get ableist treatment from that teacher. I was questioned about my condition constantly because it isn’t visible. I felt discouraged by my own medical trauma. The staff member later left, and I gained some confidence back in the classroom. However, the damage was already done.

Jasmine (far left), Ms. DiMonte (middle), and Life (right) taking a selfie together.

I know other students and staff like my teachers, Coach Cain, and advisor Ms. DiMonte have always been supportive of me and treated me with respect, but I do believe that educators can do more to support disabled students. Here are some of the things I encourage teachers to do:

- Learn more about invisible disabilities and how you can be an ally to students with them.

- Take quick action if a student confides in you with a situation where they experienced ableism from another staff member. Listen to them and work to hold your coworkers accountable.

- Make sure you and anyone else who works with disabled students at your school are informed about your students’ disabilities and accommodations. It is exhausting for us to explain our disabilities over and over again.

- Don’t force students to participate in activities. Staff were often not able to see that I was physically unable to participate in exercises.

- Check your assumptions about students that don’t participate in certain activities. Staff have reacted to me like I’m not paying attention or just lazy. In reality, I’m just a quiet, disabled student who is trying her best to accommodate herself in a system that cannot accommodate her.

Ultimately, though, I believe the best way for a teacher to support their disabled students is just to directly ask the student: “What can I do to help make this class more comfortable and accessible for you?” Truly, all students with disabilities want is to feel appreciated and listened to.