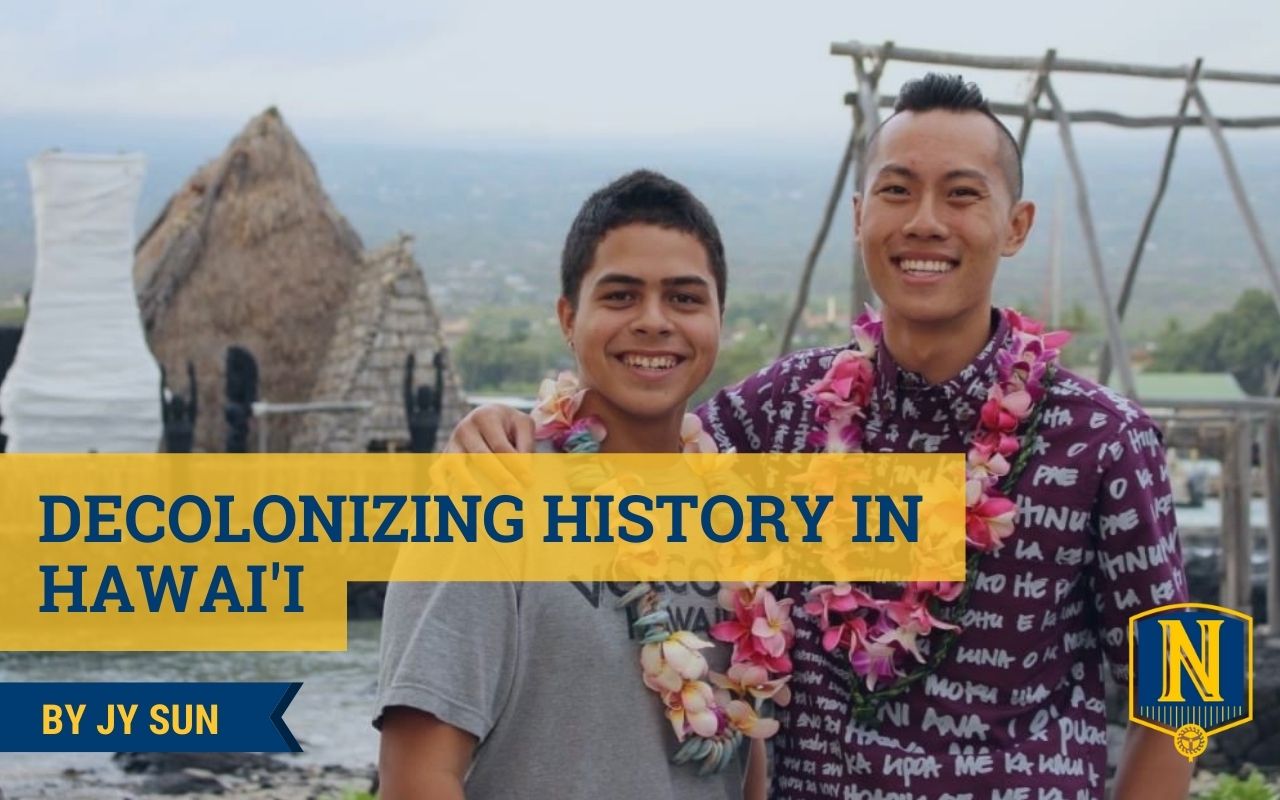

BY JY SUN, they/them, Director of College Analytics & Insights

In the summer of 2014, I landed in Hawai’i “ready” to be a high school teacher. I was a queer, non-binary, Taiwanese, American-born kid raised in what I like to call the “doldrums” of the east-coast middle-class suburbs. Outside of attending weekly Chinese school on Sundays, most of the people I saw and interacted with in my daily life were white.

When I look back, I wish that younger me had more prominent examples of Asian or queer role models in my life earlier on. It wasn’t even until college that I had Asian teacher. This was part of what drove me to choose Hawai’i when I decided to become a classroom teacher. I wanted to work with students and within a community with whom I shared some of the same lines of identity. And if I was going to do that in the United States, then Hawai’i was the place to do that.

I ended up heading to Ka’ū, a district located on the southside of the Big Island.

My view on the everyday drive to Ka'ū High and Pahala Elementary School, 2015.

Ka’ū is not just a deeply beautiful place, but also an incredibly rural place with the remnants of American colonization etched all over it. While the people in Ka’ū are predominantly a mix of Native Hawaiians, the district is home to a diverse group of people. Recent immigrants from the Marshall Islands and the Philippines and white Americans from the mainland live there. Hawai’i’s history of labor migration, driven by the American sugar industry in the 1800s, has also resulted in many residents who trace their ancestry to Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese roots.

It was in Ka’ū that I took my first step into teaching and learned the importance of decolonizing history for my students so they could find their voice and advocate for their communities.

CREATING A CLASSROOM VISION OF DECOLONIZATION

Halfway through my first year of teaching, I asked the scholars in my United States and Hawaiian history classes why it’s important to study history. In short, their answers were underwhelming. The most common responses were various versions of “so we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past.”

My own experience has shown me that most people, not even just students, interpret history quite narrowly. We default to seeing history just as a compilation of dates, events, people, and turning points. As evidenced in my students’ responses that first year, this type of teaching of history results in some pretty uninspiring reasons for why it’s important to understand our past in a deeply critical and nuanced way. I felt like I had failed to show my students that history teaches us important things about race, class, power, and oppression dynamics and how they affect us today. I felt no closer to transforming them into the leaders who would be able to advocate for change.

After that first year, I vowed that my students would not be among those who fell into this shallow misinterpretation of history. I needed my students to see how the threads of history are interwoven within their lives and their communities. I knew that the effective study of history in this critical manner hinges on including student identity, which is woefully absent in educational curricula, and I saw a detachment from identity and self in most of my 130 students that first year. So, I began the process of rebuilding our classroom into a decolonizing space, in partnership with my students.

Gearing up for my second year of teaching on school grounds in Pahala, Hawai’i in summer 2015 with my good friend and former colleague (both at Ka'ū and Noble), Sandy Tran.

The first step of this rebuilding required me to purposefully hone my classroom vision to center the unpacking of systemic oppression in Ka‘ū and within Hawai‘i.

I wanted to address all these big and seemingly intractable issues and topics with my students. I wanted us to dissect dominant American values as elements of white supremacist culture and identify where that shows up in our school in Ka’ū. I wanted us to experience what it feels like to decolonize our minds through reading the words of Native Hawaiian activists and seeing what it truly looks like to unapologetically defend one’s culture and land from colonization. I wanted us to not just be able to recall a definition for intersectionality, but to know how being Marshallese and an immigrant and queer has impacted one’s life experiences.

I knew that doing all of this was going to be a tall order and that in order to be successful, I would have to be clear about my goals.

So, I established three big ones:

- To help my students understand history as a means towards liberation and anti-oppression

- To lead my students in developing a “liberatory consciousness”

- To make sure my students left with the ability to advocate for themselves and their communities outside the classroom

HISTORY AS A MEANS OF LIBERATION AND ANTI-OPPRESSION

“I study history because I am a kanaka. My people are a dying race and the present generation of kids my age who are also kanaka are lost. History holds many secrets about my people. The reason a kanaka’s common knowledge have become secrets to our people is because Americans came to Hawai‘i and took our culture and knowledge away. I study history and government to bring my people back.”

– John, a former student in my Modern Hawaiian history class

I told myself I would make the following true for my students on a daily basis:

They will engage in deep discussions which interrogate the history, the issues, and the power and privilege dynamics that are at play. They will engage with rigorous and meaningful texts and write about them. They will understand where they fit in the world. Through doing these things, I knew that they would gain the tools to work towards their own liberation and fight against oppression.

I quickly learned that text choice in classroom spaces can be vital for lifting the veil on oppression. In my Political Science & Government course, we tied together LGBTQ+ issues like marriage equality and the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy to the ongoing impacts of the American military presence in Hawai’i by reading queer critiques of those policies. This opened a dialogue about the anti-black, colonial, and militaristic tendencies and history of these policies, while also fitting into the local context of Hawai’i.

In my Hawaiian History class, we engaged with rigorous, culturally-relevant, and meaningful counter-narrative texts, including ones written in the Hawai’i Pidgin English—a language prevalent in Hawai’i today as a relic of the exploitative sugar plantation era. We analyzed pidgin’s history as the language of the colonized and its historical alignment with the Hawaiian language and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as stigmatized languages. We discussed how that intersects with their identity as Hawaiians or pidgin speakers. In a speech he wrote and gave to an audience of my fellow educators, Ka’ala, one of my former students, put it this way at the time:

“In reality, I feel like my people and I are being oppressed by society and its institutions. Schools teach us that we all have an equal opportunity, but the truth is, as a Hawaiian, I do not. Unless we are completely fluent in proper English and proficient in subjects that have little to no connection to my cultures and traditions, this equal opportunity is little more than a myth. The educational system as a whole remains unaccommodating to my people. When you’re trying to accomplish your goals in life, that’s quite an internal conflict to be battling: ‘Success’ or identity.”

With Ka’ala in Kailua-Kona, Hawai’i in May 2016.

DEVELOPING A LIBERATORY CONSCIOUSNESS

“I study history to better understand the events that happen around me today and find a way to not be stuck in a system where I am forced or pressured to conform to the ideals of the society. I want to be able to have my voice and not be suppressed. I want society and the future to be an equal and just place for all types of people—not only those born with power and privilege. This is why history matters to me — I live in a society that history has changed. Some of those changes are great, but for those that are not, I want to be informed, so that I can change the path that has been set for me.”

— Chloe, a former student in my Democracy class

With this liberatory framing of history in hand, I then focused on the steps I needed to take as an educator to develop within my students a “liberatory consciousness” – a consciousness that is characterized by the awareness of living in a world that contains systems of oppression without becoming pessimistic.

To help my students develop this consciousness, I worked to make the following true for them on a daily basis:

Once they understand the history and issues, they will develop their own opinions of where they stand so that they can voice them. They won’t regurgitate what others have pontificated on about events throughout history, but rather make meaning of them for themselves so that they can speak up and speak out.

The Socratic method proved to be a powerful tool for my students to couple their analysis of these counter-narrative texts with practice strengthening their own voice and honing their viewpoints. There is a freedom in having the skills to be able to verbally articulate one’s values and perspective in a compelling manner – especially so for BIPOC students. We needed to build that agency.

And so, as a class, we held countless Socratic Seminars and dialogues around some really tough questions with no clear answers. All questions directly tied to the local context in which we all lived in Ka’ū.

In my Hawaiian History class, we debated “To what extent was the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy beneficial? And for whom?” and “Is tourism beneficial for Hawai’i and our people?” as well as “Should Hawai’i be a sovereign nation?”

In my Global Studies class, we discussed questions like, “To what extent is globalization beneficial for indigneous people?” or “When should the world intervene to stop human rights abuses?”.

I found the beauty of the Socratic method in not only seeing my students find their voices, but watching them build each other’s skills through direct and probing questioning of one another. As I was writing this post, I decided to message one of my former students, Shailei, and asked her what sticks out in her memory about the classes she took with me. This is what she said:

“My favorite will always be our most vulnerable moments in class where we would put our identity, feelings, and thoughts into our school work and conversations. I think that making it so personal but also a safe place for us, mentally and emotionally, was important for us to be heard. I believe everyone needs that kind of safe place and support, especially in this community. So, thank you for creating that for us.”

ADVOCATING BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Lastly, I focused on how I could help my students take their voice that they had grown in the classroom to the outside world, to access power and affect change in their communities.

Given my role as a social studies teacher, I was particularly concerned with helping my students grow their civic voice. In democratic society, harnessing the influence of the electorate can be powerful. The challenge for many communities that have long felt invisible is that they are either disillusioned with government, lack trust in the government, or see no value in participating in the electoral process since they do not view it as benefiting them in any concrete manner.

I wanted to make sure that my students would be able to identify and feel empowered to take action steps to improve their community and Hawai’i. At varying points, I asked myself the following questions: Once there is recognition of oppression, how do students move from developing their own opinions of where they stand to voicing them to the broader community? How can I support students’ efforts and ability to unify the community, re-build, and engage in anti-oppressive work – not divisive work?

As a result of this questioning, I started the Ka’ū High School’s Youth & Government (YAG) program as the first of many steps to encourage students to advocate for themselves. Youth & Government is a nationwide program where students brainstorm, draft, and debate mock legislation.

In our first year, we were the first delegation from the Big Island at the state conference in over ten years. By our second year, Ka’ū was the largest delegation in the entire state.

My first cohort of Youth & Government students at the Hawai’i State Capitol in Honolulu, March 2016.

My second cohort of Youth & Government students, March 2017.

My students at the time expressed why doing this work mattered to them:

“I’m doing this because there are things in my community that need improvement and, by having a voice in Youth & Government, I could make that change happen.” – Brennen N.

“To have a chance to express my opinion, understand inequalities and injustices, and have the chance to make a difference.” – Kaiminani R.

“To become a more informed and empowered person and to learn to make a difference, not only in my community, but on a national level.” – Aislinn C.

“I want to hear everybody’s voice and our voice can change our society. Everyone should have a chance to speak on their opinion and I feel like YAG can help me understand that my opinion can be shared out.” – Travis T.

SOME FINAL WORDS

I wanted to end this piece by giving some of my former Asian American & Pacific Islander students the final word. I reached out to several of my former students who are now at varying points in their lives to ask them to reflect on what stood out to them about their time in my classes.

Rowlie, who is graduating from Georgetown University this month and heading to Tulane University for law school this fall wrote back to me:

“During my time at Ka’ū, I had the privilege of taking JY’s classes four times. They taught me to not only understand text, but to question its intent and impact. In JY’s class, we learned from the voices of those being affected by the issues we learned about. I think moving beyond textbooks is crucial for the social sciences. Learning from speeches, books written by activists, and documentaries made my learning more impactful and interactive, in comparison to just memorizing facts in other classes. Our focus on these sources modeled the kind of learning and writing I experienced in college, and therefore, prepared me for the kind of academic style of writing I used in college.

The things I learned in Sun’s classes still stick with me everyday nearly six years later. Our knowledge of contemporary issues not only allow us to be better advocates for our communities, but better intersectional allies. Sun’s classes taught me that history is more than just preventing the “repeat of past mistakes.” It is about informing communities to know their roots and identities in hopes of empowering them to create impactful change.”

And Ka’ala who is enrolled at the University of Hawai’i in Hilo, wrote:

“The thing that sticks out the most to me is how considerate Mx. Sun was about what they taught. They took the extra step to familiarize themself with our Native Hawaiian history so that they would be better qualified to teach Native Hawaiian students about their own history. They would show up with extra, supplementary resources and articles to make the material relevant and relatable. It doesn’t seem like a whole lot but it’s something that’s stuck with me and I’ve always appreciated.

It wasn’t until I was in Mx. Sun’s class that I had ever thought of my identity. Mx. Sun’s class was the first class where I feel like I was treated as someone who was capable. They treated me like I wasn’t just some poor, angry kid but a young man with worth and potential. Honestly, it was life-changing.”